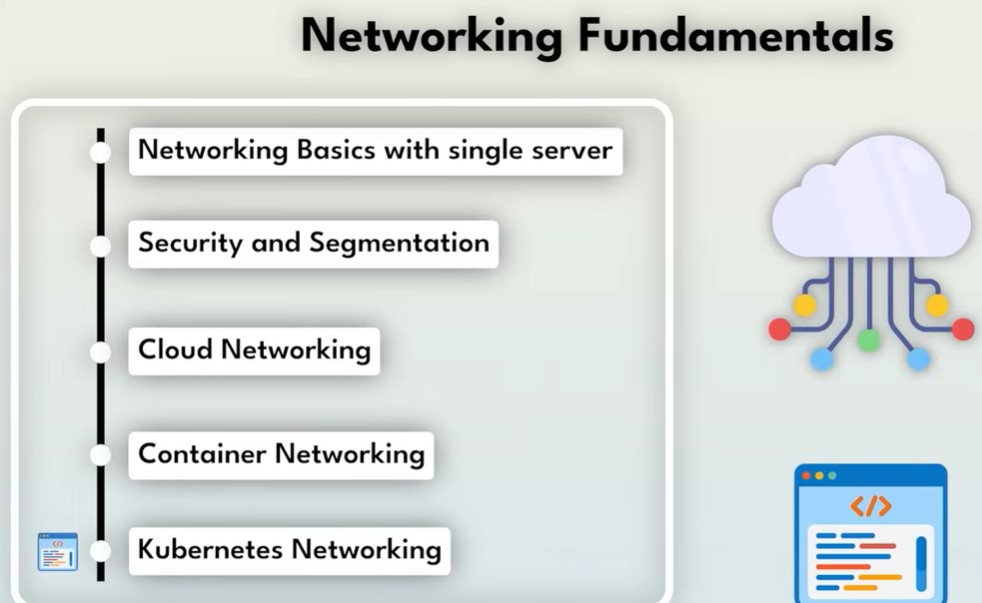

Networking is a foundational skill for every software engineer. To truly understand why networking concepts exist and how they solve real problems, it helps to see them in action rather than learning them in isolation.

In this article, we follow the growth of an imaginary travel booking platform called TravelBody. As the application evolves from a single server into a complex cloud-native system, we introduce each networking concept exactly when it becomes necessary.

From a Single Server to the Internet

When TravelBody was first launched, the entire application ran on a single server. This setup was simple, but it immediately raised an important question: how do users find the server on the internet?

IP Addresses: Identifying Devices on a Network

Every device connected to a network needs a unique identifier so other devices know where to send data. This identifier is called an IP address. It works much like a physical home address: without it, no data can be delivered.

TravelBody’s server was assigned a public IP address, allowing any device on the internet to send requests to it.

DNS: Human-Friendly Names for Machines

Remembering IP addresses is impractical, so we use DNS (Domain Name System) instead. DNS translates easy-to-remember domain names into IP addresses.

When a user types travelbody.com into a browser, DNS automatically finds the corresponding IP address and connects the user to the correct server. This is similar to selecting a contact name on your phone rather than dialing the full phone number.

Multiple Applications on One Server

As TravelBody grew, the single server began running multiple components:

-

The customer-facing website

-

A database storing booking data

-

A payment processing service

All of these applications shared the same IP address, which created another problem.

Ports: Directing Traffic to the Right Application

Ports solve this issue. Ports are numbered communication channels on a server, ranging from 1 to 65,535. Each application listens on a specific port.

For example:

-

Web application: port 80 (HTTP) or 443 (HTTPS)

-

MySQL database: port 3306

-

Payment service: port 9090

When traffic arrives at the server, the port number tells the operating system which application should handle the request. An IP address identifies the building, while ports are like apartment numbers inside it.

Improving Security with Network Segmentation

Handling customer payments and personal data on a single server introduced serious security risks. If an attacker compromised that server, they would gain access to everything.

Subnets: Dividing the Network

To reduce risk, TravelBody introduced network segmentation using subnets. Subnets divide a network into isolated sections, each serving a specific purpose:

-

Public subnet for frontend servers

-

Private subnet for application servers

-

Isolated subnet for databases

This separation limits access and reduces the impact of a potential breach.

Routing: Connecting Network Segments

Once subnets exist, they need a way to communicate. Routing determines how data moves between network segments, much like a GPS finding the best path from one location to another.

Controlling Traffic with Firewalls

Just because networks can communicate does not mean they should. This is where firewalls become essential.

Firewalls: Enforcing Security Rules

A firewall inspects network traffic and allows or blocks it based on predefined rules.

There are two main types:

-

Host firewalls, which protect individual servers

-

Network firewalls, which filter traffic between subnets

For example:

-

The database server may only allow incoming traffic on port 3306 from the application subnet

-

The frontend subnet may only allow incoming internet traffic on ports 80 and 443

This layered security approach ensures attackers must pass multiple checkpoints to cause damage.

Private Networks and Internet Access

As TravelBody expanded, it added dozens of backend servers running in private subnets. These servers used private IP addresses, which are not accessible from the internet.

NAT: Secure Outbound Internet Access

Private servers still need internet access for tasks like:

-

Downloading updates

-

Calling external APIs

Network Address Translation (NAT) solves this problem. NAT allows multiple private servers to share a single public IP address for outbound connections.

When a private server sends a request:

-

The NAT device replaces the private IP with its public IP

-

The request goes to the internet

-

The response is mapped back to the original server

This keeps servers hidden while still allowing outbound communication.

Moving to the Cloud

Managing physical servers became expensive and slow. To improve flexibility, TravelBody moved to the cloud, renting computing resources instead of owning hardware.

Networking Concepts Remain the Same

Although the infrastructure changed, the networking fundamentals did not. The cloud still uses:

-

IP addresses

-

Ports

-

Subnets

-

Routing

-

Firewalls

-

NAT

In the cloud, these are provided as managed services.

Virtual Private Cloud (VPC)

A VPC is an isolated section of a cloud provider’s network, similar to renting a private floor in a large office building. Inside the VPC, TravelBody recreated its familiar architecture using public and private subnets, routing tables, internet gateways, and NAT gateways.

Containers and Application Portability

As the application evolved into a microservices architecture, deployment complexity increased. Differences between development and production environments caused frequent issues.

Containers: Packaging Applications

Containers package everything an application needs—code, runtime, libraries, and configuration—into a single portable unit. This ensures the application runs consistently across environments.

Docker was used to containerize all TravelBody services.

Container Networking

Containers communicate through:

-

Bridge networks for communication on a single host

-

Port mapping, which exposes container ports through the host server

-

Overlay networks, which allow containers on different servers to communicate as if they were on the same network

These mechanisms resemble earlier concepts like NAT and routing, applied at the container level.

Kubernetes: Managing Containers at Scale

As TravelBody grew, it began running hundreds of containers across many servers. Manual management became impossible.

Pods and IP Addresses

In Kubernetes, containers run inside pods. Each pod gets its own IP address, and all containers inside a pod share that address.

However, pods are temporary. They can be created, destroyed, or moved at any time, and their IP addresses change.

Services: Stable Networking for Dynamic Pods

To solve this, Kubernetes uses services. A service provides:

-

A stable IP address

-

A stable DNS name

The service automatically routes traffic to healthy pods behind it, even as pods are replaced. Applications connect to services rather than individual pods.

Exposing Applications with Ingress

To make services accessible from the internet, Kubernetes uses Ingress.

Ingress acts as a centralized entry point, routing incoming requests to the correct service based on rules such as domain names or URL paths.

For example:

-

Requests to

travelbody.comgo to the website service -

API requests go to the booking or payment services

Key Networking Fundamentals Recap

By following TravelBody’s journey, we uncovered five essential networking concepts:

-

IP addresses and DNS – Identifying devices and translating names into addresses

-

Ports – Directing traffic to the correct application

-

Subnets and routing – Structuring networks and connecting segments

-

Firewalls – Controlling and securing network traffic

-

NAT – Allowing private systems to access the internet securely

These fundamentals apply everywhere: physical servers, cloud environments, containers, and Kubernetes clusters. While tools and platforms change, the core principles remain the same.

Mastering these concepts allows engineers to understand, design, and troubleshoot systems at any scale.